Note: This post was co-authored by Chad Michel. The rest of this 5-part series can be found here:

Part 1 – What and Why

Part 2 – Leverage Your Leadership Roles

Part 3 – Maximizing Productivity

Part 5 – A Layered Approach To Quality

In the fourth part of our series, we will be building on the what’s and why’s of funability, how to leverage your leadership roles, and ways to maximize the productivity of your engineers by covering how development processes can incorporate more satisfaction into daily work and contribute to a rewarding workplace culture.

Design Identity (Have One)

The concept of having a consistent design identity goes back to the early days of Don’t Panic Labs. Since the beginning, our vision included having several projects going on simultaneously. This meant finding ways to avoid treating each new project as a unique design effort. We needed commonality.

When done properly, the design methodologies employed (e.g., object-orientation, service usage, micro-services, IDesign concepts) in every project should be so similar that they look like they were all created from a single mind.

In his classic book The Mythical Man Month, legendary software engineer Fred Brooks said, “I will contend that Conceptual Integrity is the most important consideration in system design. It is better to have a system omit certain anomalous features and improvements, but to reflect one set of design ideas, than to have one that contains many good but independent and uncoordinated ideas.”

In other words, given that we are building software that (hopefully) will be extended and maintained for years, having a system that has no shared or controlled design or, worse yet, where all design decisions are left to individual developers, will surely lead to software “rot.”

Clearly, there needs to be some sort of design. But too often, especially in the startup world, there is a push to move fast and skip the design step. While this may feel good at the beginning because it keeps the forward momentum, whatever benefits you think you are realizing will end quickly.

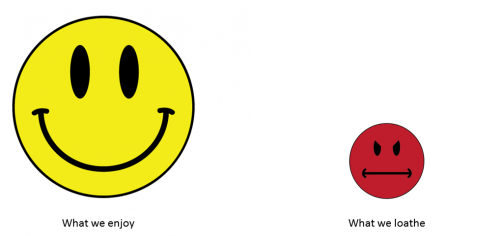

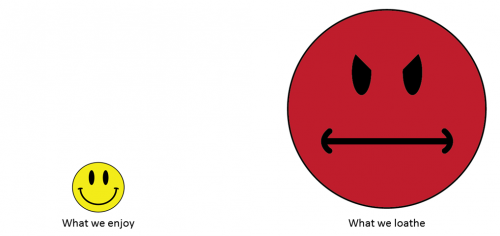

Martin Fowler addresses this exact phenomenon in what he calls his Design Stamina Hypothesis (see below).

In his experience, as well as ours, it doesn’t take you long to begin reaping the benefits of having good design. See that point where the “good design” and the “no design” lines cross on the “design payoff line”? That usually happens in just a matter of weeks, not months. This is why we believe that if you’re working on a project that’s going to last longer than a few weeks, you’re better off investing in a software design/architecture exercise. That relatively little bit of effort to make the experience of working on that code more enjoyable.

To sum up, here are some of the benefits we’ve realized by having a consistent design identity:

Testability. Perhaps we’re stating the obvious, but quality assurance is made much easier when a shared design identity exists. If several systems share the same methodologies, they naturally become much easier to test. A sort of rhythm is found by the engineers. They become instinctively aware of where possible problems may arise. They build the system with this knowledge in mind, avoiding many pitfalls that would typically ensnare a one-off system. But if a problem does arise, troubleshooting is typically quick. This keeps the project moving forward. It also keeps product quality high. And those make for happy engineers.

Flexibility. Not only does this mindset save time, it also makes it easy for environments (like ours) where engineers may be moved around. By using shared programming models, methodologies, processes and patterns, it’s easy for us to take an engineer from one project and put them on another. We only need to spend a short amount of time showing them the architecture diagrams and discussing which services are implemented. We then send them on their way. This makes for a very efficient environment that consistently keeps the “getting started” frustrations to a minimum.

Repeatability. And this has helped us throughout our diverse portfolio of projects. Whether it is a motion capture and 3D imaging unit that tracks weight-training athletes (EliteForm) or a data-heavy infrastructure management system (Beehive Industries), shared design processes have helped move these projects much faster than building two separate products from the ground up.

Practice Test-Driven Design

In a previous life, both of us worked together at an e-commerce company. The core software was not developed with funability in mind and it was – for lack of better adjectives – a train wreck. It was difficult to maintain and it was difficult to deploy. Basically, it was not enjoyable.

We came to the realization that a rewrite was required so it could be more efficiently maintained in the future. While we initially didn’t want to take this project on, it became apparent very quickly that it was becoming one of the most enjoyable experiences we’ve ever had. We took what we had learned in the past and thoughtfully constructed this new system. We made unit testing a priority and we had numerous tests around the entire code base. We were feeling good about it.

And we needed that confidence because one day, the old system just collapsed. It was a goner. So that seemed as good of time as any to roll out the new system. And it was a fairly painless rollout, but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t scary. We didn’t think that we were ready for a rollout, but when we considered the number of tests we constructed along the way, it instilled a lot of confidence. So from that day forward, we’ve been sold on the idea of test-driven design.

One reason why we believe so strongly in test-driven design is because it forces consumption awareness in the code, because you, as a test writer, are the first consumer of a class/service/method. It focuses you on the interface rather than the implementation. And when you become the first consumer, it makes you consider aspects you might not have before (such as decoupling the code to make it more testable and facing areas head-on you may have otherwise skipped because of its high level of difficulty).

Implementing unit tests forces the engineer to be more empathetic about the code they are writing. It’s perspectives like that which makes life easier for the people who will be maintaining the code in the future. When you have to describe the intent of your code, you can be led to think differently about how you’re going about it. Sometimes the only way to really get your point across is to write example code. Even better. Taking time to document as much as you can lay the groundwork for an enjoyable system later. One of our favorite developer maxims holds true for tests as well as the code itself: “Always code as if the guy who ends up maintaining your code will be a violent psychopath who knows where you live.”

Testing also allows you to run “what if” games around your code. If you’re planning wide-reaching changes to your system, testing helps you proactively assess the impact. These exercises can be quite fun, especially if you’re the type of engineer who obsesses about performance and efficiency.

There’s Still More

In this post, we covered the importance of processes that help achieve funability through various design processes. In our next post, we’ll cover how various layers of testing can produce quality software and – in turn – provide funability for the team.

This post was originally published on the Don’t Panic Labs blog.